I’ve always loved plants, especially those I can easily propagate and grow in jars or small pots in my bedroom, but since moving to the UK my room has looked a little less green than I’m used to. It’s no surprise then that I’ve recently fallen in love with a plant so ubiquitous (yet somehow overlooked) in British landscapes, the ‘common ivy’ Hedera helix. Hopefully here I can illustrate some of the fascination I feel. Aside from brilliantly adorning trees, walls, and sculptures all year round as an evergreen, the biologist in me marvels at the huge diversity it displays in its leaves. Even among nearby plants H. helix can show great contrast in leaf colour, shape, size, texture, and variegation with some leaves displaying fantastic Rorschach-like patterning. As a testament to its hardiness, one cutting that I’ve growing next to me was found emerging from a chunk of chalk at the Cherry Hinton chalk pits.

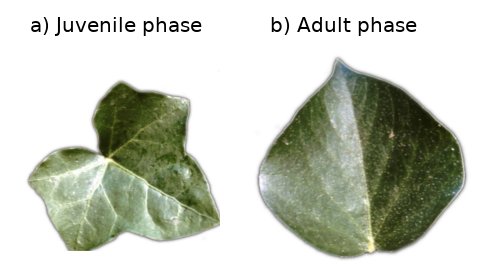

These morphological changes can even occur within the same plant, with a distinct separation between the juvenile and adult life cycles. The former is marked by lobed leaves and herbaceous growth. This is in contrast to the adult stage defined by the formation of a woody climbing structure and unlobed leaves with hermaphroditic flowers appearing a few metres above ground. Stems and leaves in both these stages can appear simultaneously in the same plant, and it is not uncommon to see adult phase growth firmly climbing a tree while the juvenile foliage billows around the base. This morphological shift is known as an epigenetic modification as it is due to changes in the expression of the plant’s genes, rather than a mutation in the genetic code itself. This is analogous with the tissues of our brain and heart having the same genetic material, yet still displaying different shapes and functions due to the respective differences in gene expression.

Juvenile and adult H. helix leaves, adapted from Sandra B. Wilson.

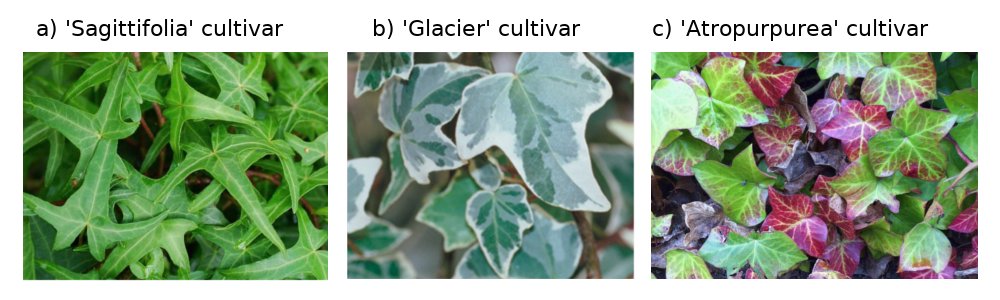

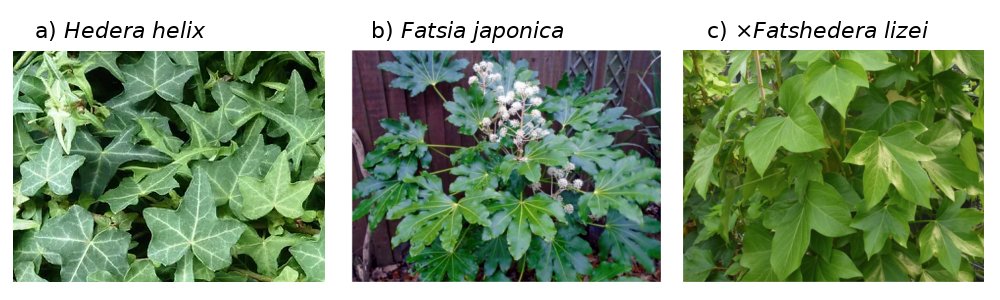

In addition to the common English ivy there are ~12 other species In the Hedera genus distributed across the rest of Europe, North Africa, and Asia, with even one exclusively present in the Canary islands (H. canariensis). Even in H. helix itself there are over 30 documented cultivars mainly differing in leaf shape with some exceptionally pointy (‘Sagittifolia’), or colours ranging from icy white and green (‘Glacier’) to rich purple (‘Atropurpurea’).

A hybrid known as ×Fatshedera lizei also exists between H. helix and the Japanese paper plant Fatsia japonica, which was crossed once in a French nursery in 1912, and having not since been repeated is now maintained by propagation. While H. helix is a vine and F. japonica is a shrub, ×F. lizei appears to have the intermediary qualities of both, being able to grow as a shrub to 1.2 metres tall, in addition to up to 4 metres as a vine with structural support. This is quite notable as the paperplant is from an entirely different genus, and no hybrids between the more closely related H. hibernica and H. helix have ever been created or observed. It is currently thought that lots of the current species diversity among Hedera emerged as a result of hybridisation via allopolyploidy, with a species originating in the Mediterranean basin believed to be the most recent common ancestor. It has also being shown that the global diversification of taxa is relatively recent due to the low levels of sequence divergence between them.

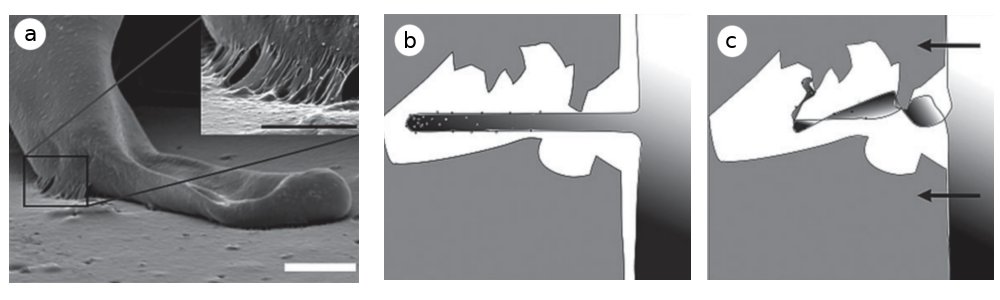

Another aspect of English ivy that makes it a great hobby and house plant is how readily it creates adventitious roots. These are roots that form out of non-root tissue such as stems, and in general are used by plants to provide an additional way to spread without reliance on the established root system. For the naturalist, adventitious stems provide an easy way to propagate plants since the required roots have already been generated, albeit with a waxy coating to prevent desiccation. In H. helix these extra roots are what allows it to climb 30 metres tall on walls and up to 90 metres by adhering to trees. Like feelers, after making contact with a solid structure the adventitious roots of ivy grow even smaller hairs just about as large as the eye can make out that penetrate any available groove or crevice. From these hairs a biopolymer adhesive substance is excreted which effectively glues the fine hairs and the plant to the structure. In other plants this substance (arabinogalactan) is also used as a glue by the plant to seal its wounds. Finally, these root hairs are then selectively desiccated by the plant on a single-cell level, with the change in form caused by their shrivelling pulling the main body of the plant in tight with the structure and sealing them together.

Ivy root binding and adhesion, adapted from Melzer, 2010.

By cultivating some of the divergent samples of ivy that I find, I’d like to determine how much intra-organism variation exists. Then by isolating and replanting deviating sections within the same plants, I’ll be able to tell whether mutational or transcriptional changes encoding the different morphologies are generated in the stem as it grows, or whether they occur spontaneously in the leaves. Additionally, if the changes are local adaptations they may start reverting depending on where in my room they are placed. If not, perhaps having different looking leaves assists them in another respect, for instance maintaining consistent energy supplies with the varying amounts of light available, or protection from insects. I challenge you next time you’re walking to keep an eye out, you’ll start seeing them everywhere. If you spot any that are exceedingly divergent please send me snap!